Reading is easy. It’s something you learn early on at school and then use for the rest of your life. But, most of the time — we don’t read well. We read sufficiently. We pay the text just enough attention to get what we need out of it. We leave so much meaning unused. But, sometimes we find a text that has more to offer than a merely sufficient reading will yield. Perhaps it’s a book that means a lot to you, an article that has something really interesting to say, or even something you have to read for school or university. A text like that, we need to read well. I think reading something well is more difficult, but ultimately more rewarding. Reading well requires time, commitment, and determination, but most of all — it requires a method. I’ve developed a method of reading that I’d like to share with you. I developed it when I was studying law at UCT and had to learn how to decode really dense texts and be able to understand them thoroughly. Since then I’ve continued to use it in my professional life as an attorney and for my hobbies as someone who’s interested in understanding things properly.

Reading is easy. It’s something you learn early on at school and then use for the rest of your life. But, most of the time — we don’t read well. We read sufficiently. We pay the text just enough attention to get what we need out of it. We leave so much meaning unused. But, sometimes we find a text that has more to offer than a merely sufficient reading will yield. Perhaps it’s a book that means a lot to you, an article that has something really interesting to say, or even something you have to read for school or university. A text like that, we need to read well. I think reading something well is more difficult, but ultimately more rewarding. Reading well requires time, commitment, and determination, but most of all — it requires a method. I’ve developed a method of reading that I’d like to share with you. I developed it when I was studying law at UCT and had to learn how to decode really dense texts and be able to understand them thoroughly. Since then I’ve continued to use it in my professional life as an attorney and for my hobbies as someone who’s interested in understanding things properly.

Read it

The first step is to read the text as one normally would. This is to give you an overview of its central argument as a whole. Hopefully, you’ll find it easier to read something the first time knowing that you’re going to come back to it and read it again in much more detail later. This is your first pass – a chance to read the text at your leisure without the pressure of having to extract sufficient meaning at your first brush. It’s about familiarising yourself with the text and getting comfortable with it, not about scrutinising it and making sure you understand everything. Don’t worry – that comes later.

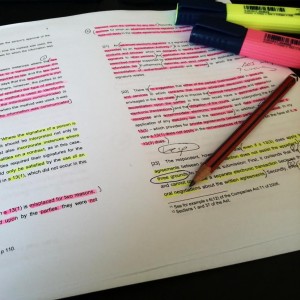

Mark it up

The next step is to make notes on your text. You need to read it again and stop and mark your text where appropriate in ways that are relevant to you. I like to do this physically by printing it out and using some hi-lighters. I generally only use four, but go ahead and use as many as you see fit. The idea is to use each different colour to represent different functions in the text. (You could also do it digitally on a computer using a mark-up function like the hi-lighting or sticky notes feature in something like Adobe Acrobat Reader.) This may sound a bit strange, but if you already have a method of classifying text by function – it becomes much easier.

As a law student we were prescribed a method for classifying text by function. This method makes sense to me because I’ve used it for a long time, but you may need to come up with your own. I’ve adapted it over the years, but it basically involves dividing text into four functions:

- The facts – The facts are the undisputed elements of the text. They are the premises that the writer has obtained from elsewhere and presents verbatim. They may have rephrased them in their own words, but by and large they are other people’s ideas that they are relying on.

- The issues – These are the questions that the writer is trying to resolve in their text. They may be implied instead of stated explicitly.

- The reasoning – This is the writer’s argument. They are the steps that they take to make up their mind. They usually follow a logical sequence and it may make sense to number them in a way that leads up to a particular conclusion.

- The conclusions – These are the answers to the questions that the writer ends up getting to.

Condense it

The next step is to condense the text. You want to come up with a set of semi-arbitrary restrictions and use them to summarise your text. For example, you may decide that you wish to summarise it in no more than a specific number of sentences. I like to take a piece of lined paper and divide the number of lines on each side of the page between the pages of the text I’m reading, for example so that each page has to be condensed onto two lines. You can even do this with a whole book where you take a lined exercised book and decide that you’ll summarise each chapter in no more than two pages. This step is very important because it lets you be creative in summarising your text. Restriction breeds creativity. Being creative with knowledge helps you absorb it. If you had let yourself use any number of lines or pages to summarise your text, there would be less incentive to rethink it and distill it into a more condensed form using your own words.

The result of this condensing process is a curated index to your original text. This summary has an added bonus — you can quickly refer to it and work out where the critical element you were looking for was in the original text.

Rewrite it

The last step is to rewrite the summary in your own words. This involves taking your condensed summary (together with the original text where necessary) and using it to summarise the key ideas of the text. This is an opportunity to restructure the text in a way that makes more sense to you than the original text may have.

Worth it

By the end of this process you should have gone through the four steps. It would have taken you longer, but for the right text – the time is always worth it. You should have read the text as normal, marked it up in a way that makes sense to you, condensed it into a restricted format, and used that summary to rewrite it in your own words. This process should have lead you to a deeper understanding of your text and the ideas it contains.